By Leo Ryan, Editor

In a historic development, the world’s first global treaty to protect ocean life in international waters entered into force on January 17, bringing into effect legally-binding rules for the sustainable use and protection of marine resources in the high seas. These immense, largely unregulated waters are bursting with rich biodiversity and critical minerals coveted by countries and industrial interests for a host of uses, including EV batteries.

Welcoming this milestone, IMO Secretary-General Mr. Arsenio Dominguez said: “The world has demonstrated that countries can come together with a common vision and build a framework to manage the ocean sustainably while ensuring its benefits are shared fairly amongst all humanity. Now we must continue working together to put these rules into action. IMO is ready to support the BBNJ implementation within IMO’s sphere of expertise.”

Formally known as the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), the treaty addresses:

- Marine genetic resources, including the fair and equitable sharing of benefits;

- Measures such as area-based management tools, including marine protected areas;

- Environmental impact assessments; and

- Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology.

Shipping and marine environment protection on the high seas

Ships trading across the world’s oceans are subject to stringent environmental, safety and security rules, which apply throughout their voyage.

IMO has developed more than 50 globally-binding treaties and other measures to support shipping’s sustainable use of the oceans, enforced through a well-established system of flag, coastal and port State control.

IMO instruments that actively contribute to the conservation of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction, include, among others:

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution by Ships (MARPOL)

- International Ballast Water Management Convention, which aims to prevent the transfer of potentially invasive aquatic species; and

- London Convention and Protocol, regulating the dumping of wastes at sea.

A new legally-binding framework is currently being developed to address shipsʹ biofouling and minimize the transfer of invasive aquatic species.

In addition, IMO has adopted numerous protective measures, including designating Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (PSSAs), Special Areas and Emission Control Areas in which a high level of protection and stricter rules apply to prevent sea pollution. IMO has also issued guidance on protecting marine life from underwater ship noise.

The BBNJ Agreement enters into force following its adoption in June 2023 – a culmination of decades of negotiations and preparatory works. More than 80 nations have ratified the Agreement to date.

Perspectives on Canada/US ratification

Although Canada, which has the world’s longest coastline and robust economic, cultural and environmental ties to three oceans – Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic – was one of the first countries to sign the High Seas Treaty, the federal Parliament has still not ratified the historic pact. But this ratification is expected to take place as soon as the current busy agenda complicated by the Trump global trade war permits.

Among the longstanding Canadian champions of protecting marine life and of the High Seas Treaty one finds Vancouver-based West Coast Environmental Law (WCEL). Since 1974, this non-profit group of environmental lawyers and strategists has been working with communities, the private sector and all levels of government (including First Nations) to develop proactive legal solutions to protect and sustain the environment.

To what degree do Canadians recognize the significance of their country’s ocean dimension? Responding to this question from Maritime Magazine, WCEL’s Stephanie Hewson shared: “A lot of people living away from the coasts may not feel how crucial the ocean is, even for their lives. But still, more and more people are becoming aware.”

In a recent, lengthy analytical report, Ms. Hewson welcomed a number of commitments from the Mark Carney government – namely its intention to ratify the High Seas Treaty, protecting 30% of the ocean spaces by 2030, establishing new protected areas, and the launching of a Canadian Nature Protection Fund.

She describes such commitments as “a good start – but as the pressures on the oceans continue to intensify, we must go further to protect the ocean from harmful and risky activities like deep sea mining, geoengineering and pollution from commercial shipping.”

U.S. ratification big question mark

Ratification by the United States would be momentous for international cooperation. But it has been historically difficult for the U.S. to ratify intergovernmental treaties, including the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which initiated a general undertaking of nations to protect the marine environment. One reason for this is the constitutional requirement that two thirds of the Senate must support ratification, not easy to attain due to the Senate’s divided politics. And especially for international environmental agreements, there is an overriding concern over multilateralism and maintaining U.S. sovereignty.

Under the former Biden administration, the U.S. signed the treaty – in fact from the outset in September 2023. But, not surprisingly, the Trump administration has not only firmly opposed ratification, it has already positioned itself to bypass the treaty’s fundamental principles by unilaterally authorizing the licensing of several deep sea mining operations for critical minerals in international waters in the western Pacific. This bypasses the obligation that any ocean mining activity in international waters should undergo an environmental assessment by the International Seabed Authority, the specialized U.N. agency established in 1994 under UNCLOS. Some analysts see this as another example of the Trump administration’s moves to counter China’s dominance of the rare earth metal market.

So, until further notice, no formal U.S. application of the High Seas Treaty.

“With the U.S. not there, I think it will be all the more important for Canada to soon ratify the treaty and offer a vital voice from North America,” stresses environmental marine lawyer Stephanie Hewson.

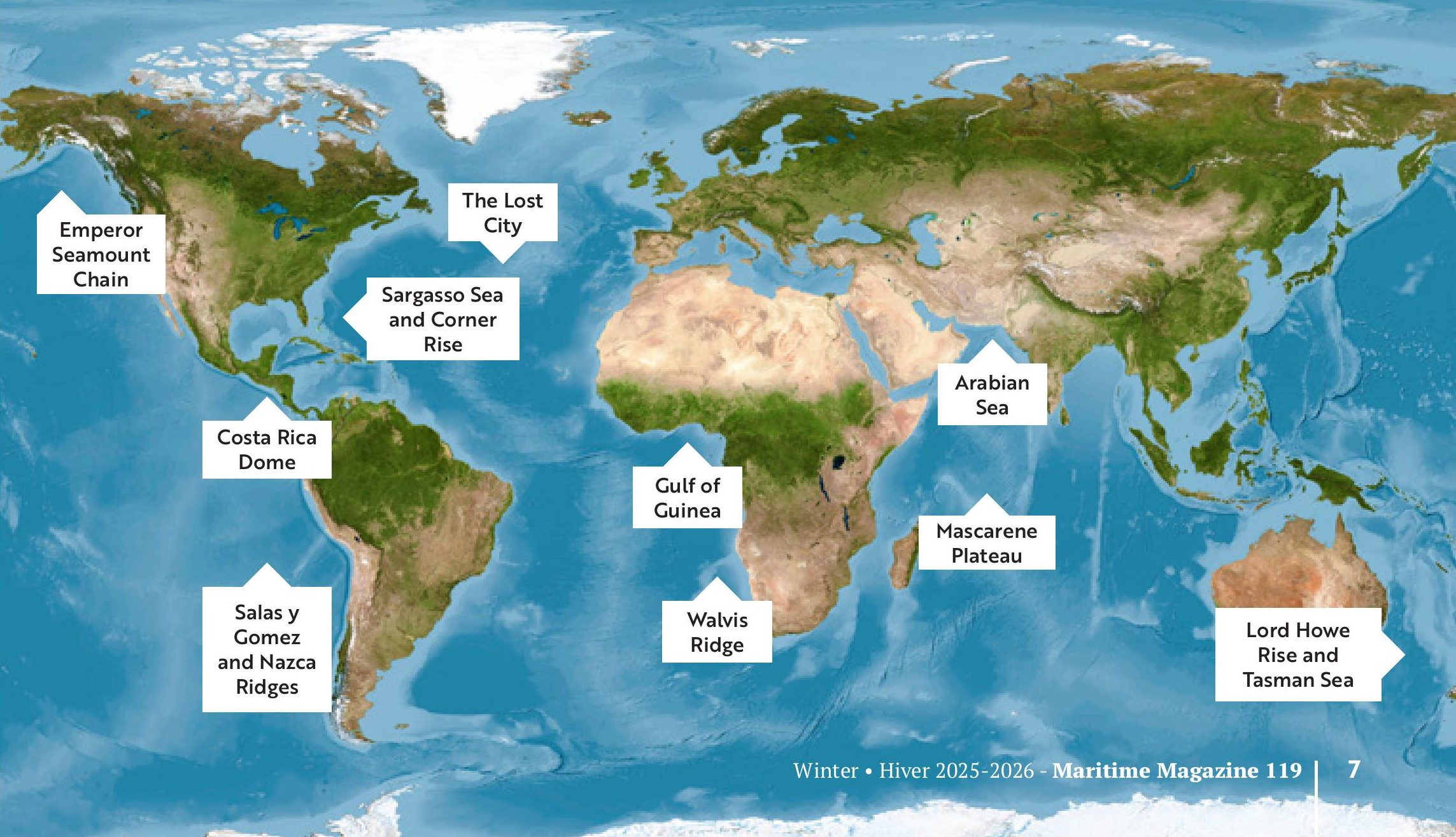

(Images show IMO photo of dolphins and Maritime Magazine screen shot of proposed marine protected zones high seas)